China Institue Gallery | Mao’s Golden Mangoes and the Cultural Revolution

March 31, 2015

This exhibit tells a story that blew my mind. It’s mango season right now, so in Chinatown in Manhattan, and street vendors are selling the fruit, 3 for five dollars. While I can hardly imagine a time and place where no one had seen a mango, that is the least unusual part of the incredible, surreal tale documented in this exhibit.

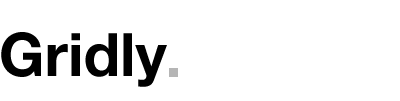

In 1966, Mao started the Cultural Revolution, and he empowered school and university students to form the Red Guard to eradicate bourgeois elements in society. By 1968, the students were fighting among themselves and against the army, and Mao sent armed factory workers into the universities to subdue the students. Around the same time, the president of Pakistan visited Mao and gave him a box of mangoes as a gift. Mao in turn gave the mangoes to the “Worker-Peasant Mao Zedong Thought Propaganda Teams” who had overpowered the red guard at a university, and who Mao had named “permanent managers” of the education system. Most Chinese had never seen or heard of a mango before.

At this point in time, Mao was taking on a god-like position in Chinese society, so a gift from the chairman to the factory workers took on symbolic meaning. The mangoes symbolized Mao’s love for the workers, and of his sacrifice — not eating this exotic fruit but giving it to the workers.

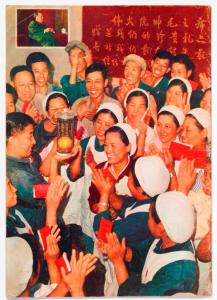

One mango was distributed to each of a number of factories, and these factories in turn had wax or paper mache replicas made and given in to each of their workers in glass cases. Owning one of these replicas was considered a great honor, and they were displayed with pride in the workers’ homes. At one factory, the original mango was preserved in formaldehyde, at another the rotting fruit was boiled in a huge vat, so that each worker could get a spoonful of the broth. The mangoes were treated like religious relics, and this tasting of the mango was a sacrament.

Mango vitrine with likeness of Mao and standard inscription: “Respectfully wishing Chairman Mao eternal life. To commemorate the precious gift presented by Great Leader Chairman Mao to the Capital Worker-Peasant Mao Zedong Thought Propaganda Teams – Mango. 5 August 1968,”

Almost immediately the mango, as Mao’s gift to the workers, became a symbol which appeared throughout China. In this exhibit, we see examples of Mango Brand cigarette packs, which became the most popular cigarettes at the time. There are mirrors decorated with mangoes, that were intended as wedding gifts. The exhibit also includes mango motifs on cups, trays and bowls. These are enameled metal, not porcelain, as they were intended for workers.

Tray with design of mango, character for “Double Happiness,” and stenciled slogan:

“With each mango, profound kindness,”

By October, only 3 months later, a float in the form of a giant basket filled with enormous mangoes figured promintently in the National Day Parade in Tiananmen’s square. This float also entered the popular imagination, and the image of a basket of mangoes was incorporated into textile designs, examples of which are also included in the show.

Tech bonus:

The exhibit includes two interesting video displays: one shows excerpts of a 1976 propaganda film, Song of the Mango, about the workers imposing peace among the students of a technical institute, and the other is an oral history with contemporary interviews with three people who lived though these events. This helps bring these artifacts and the research around them to life.

© 2026 50 MUSEUMS IN 70 WEEKS | Theme by Eleven Themes

Leave a Comment