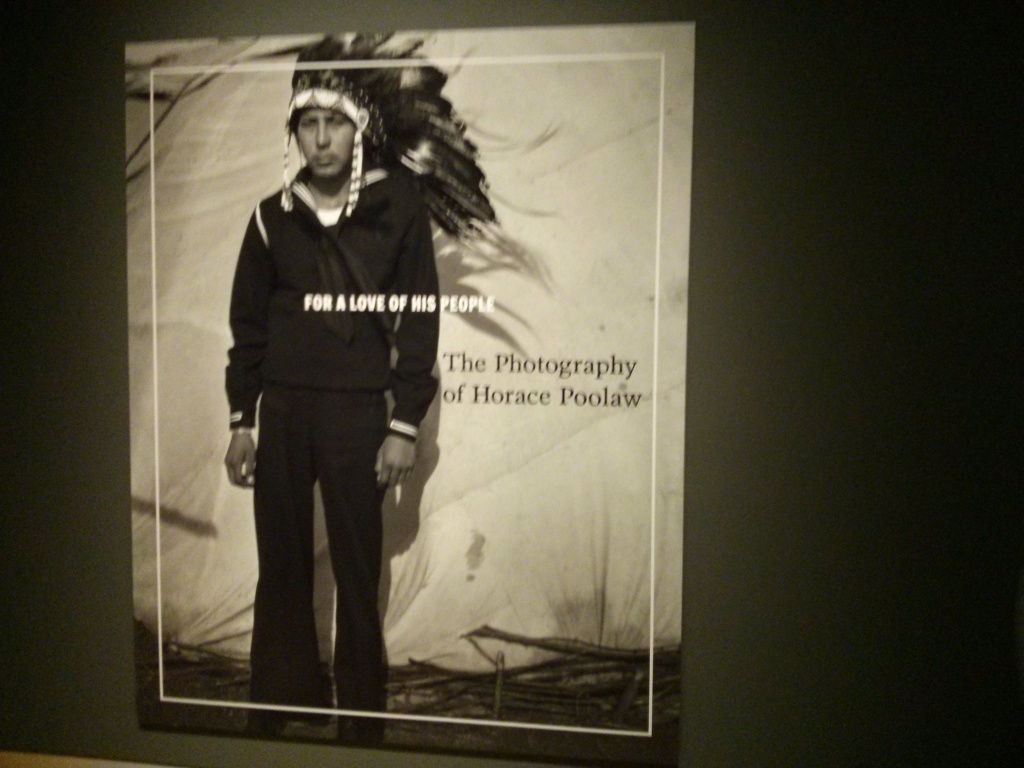

National Museum of the American Indian in New York | For a Love of His People: The Photography of Horace Poolaw

November 12, 2014

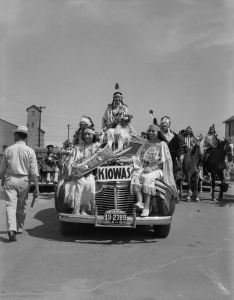

The photos in this exhibit show Native Americans from Oklahoma in the 1920’s-1960’s in ways that upend my expectations — the subjects of these photos are not the noble savage or the victim of of repression. Rather, they display traditional culture, headdresses and beaded clothing, mixed with fashions and roles I associate primarily with white people, due to the images I am used to seeing: flapper, sailor, boy scout, kids under a christmas tree or in cowboy outfits. I’ve seen these archetypes before — I have them in my own family photos — but not with Native American subjects. And the traditional garb and cultural events also seemed to defy my expectation when juxtaposed with their mid-20th century context — big shiny american cars parading with “tribal Princesses”.

Robert “Corky” and Linda Poolaw (Kiowa/Delaware), dressed up and posed for the photo by their father, Horace. Anadarko, Oklahoma, ca. 1947. © 2014 Estate of Horace Poolaw

Left to right: Juanita Daugomah Ahtone (Kiowa), Evalou Ware Russell (center), Kiowa Tribal Princess, and Augustine Campbell Barsh (Kiowa) in the American Indian Exposition parade. Anadarko, Oklahoma, 1941. © 2014 Estate of Horace Poolaw

Tech Bonus: These images were originally shot using a large forma camera, and after his death, students at the University of Wisconsin digitized and “cleaned up” the negatives, allowing for the large prints in the exhibition. The photo at the top of this post was printed over 6 feet tall, probably something that Poolaw would never have dreamed of.

© 2026 50 MUSEUMS IN 70 WEEKS | Theme by Eleven Themes

Leave a Comment